What gives us our ability to taste and smell? What can take that ability away? Is age a factor? What are the consequences of losing our sense of taste and smell? And what can we do about it?

What gives us our sense of smell (olfaction)?

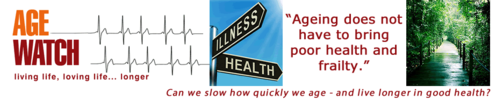

Smells are detected in the nose by specialised nerve cells known as olfactory neurones. Extending from each olfactory neurone are 8-20 olfactory cilia, hair-like structures extending though the mucous. These contain the actual smell receptors.

When an odour molecule (an ‘odorant’) binds to the cilia, it sets off a signal that travels along the olfactory nerve to the olfactory bulb, underneath the front of the brain. The brain then interprets patterns in electrical activity as specific odours – i.e., something we can recognise as a specific smell.

What gives us our sense of taste (gustation)?

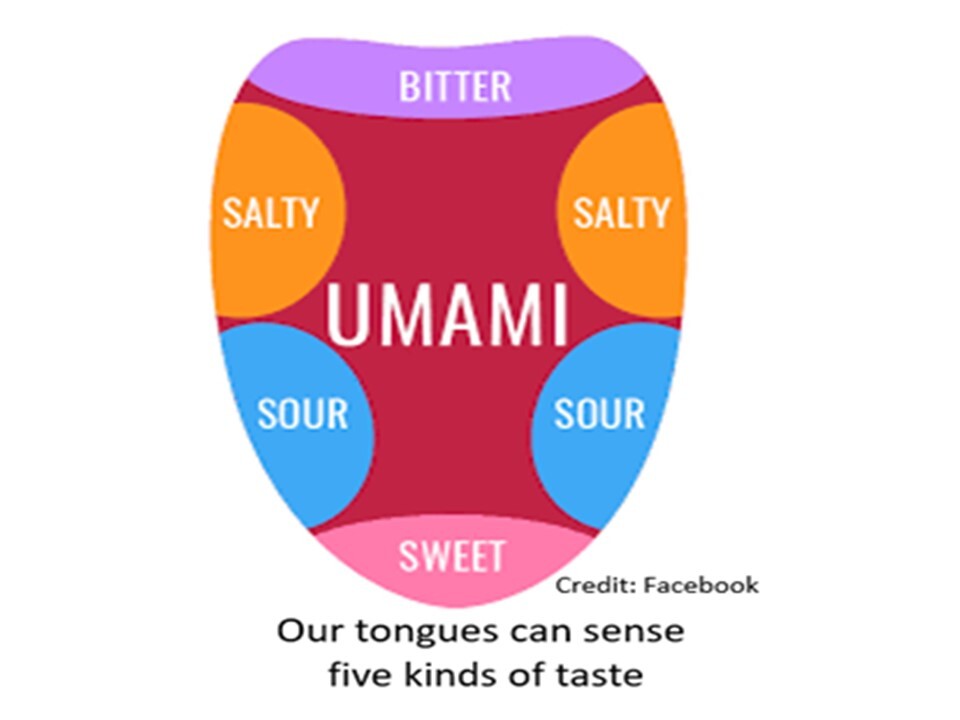

Taste helps you to evaluate what is safe to eat and drink. It also prepares your body to digest food. The taste of food is caused by chemical substances which interact with receptor cells in the taste buds on the tongue, throat and roof of the mouth. The cells send information to the brain which helps you to identify the taste.

The senses of smell and taste are closely linked. When you chew food, odour molecules enter the back of your nose and can affect taste. Information is sent to the brain from the nose and the mouth at the same time. The flavour of the food is the combined experience of taste and smell together.

What factors affect our sense of smell and taste?

Some of us may be born with a better sense of smell than others, just as some people may be born with better hearing, sight or sense of taste.

However, during our lives, many factors can influence our sense of smell and taste including:

Does our sense of smell and taste deteriorate with age?

Age may affect our ability to distinguish one smell or taste from another. Deterioration of these senses affects more men than women, and is most marked in people over the age of 70. The dulling of our ability to smell and to taste is thought to be the result of not being able to keep up with the constant loss and replacement of olfactory cells and taste buds.

Another contributing factor might be that the amount of mucous we produce in our nasal cavities and sinuses reduces as we get older. This mucous enables the cilia in our nose and throat area to clear the airways of pathogens, allergens, debris and toxins, thus maintaining our respiratory defence. Problems caused by a deviated septum may also become more acute during later life.

|

Hyposmia is a reduction in our sense of smell. Anosmia is a complete loss of smell. |

Hypogeusia is a reduction in our sense of taste. Ageusia is a complete loss of taste. |

How many older people are affected?

Up to half the US population between the ages of 65 to 80 may be affected by a loss of smell or a loss of taste. In those over 80, more than 60% may experience a reduction in sense of smell.

Of the original 10 million or so olfactory cells normally found in the nose, as many as 60% of these may be lost with age. A loss of taste, however, is less prevalent with age.

The consequences of our sense of smell deteriorating

Smell is often our first response to an unpleasant or dangerous stimulus. For instance, it:

- can alert us to fire before we see the flames.

- makes us recoil before we taste rotten or distasteful food.

- provides us with an ability to detect and avoid many poisonous or dangerous gases.

- makes us aware of our own personal hygiene.

The loss of our sense of smell affects our enjoyment and interest in food, since taste and smell are so intimately entwined. As a result, older people may show less interest in food, which can lead to a significant reduction in appetite and potential dietary deficiencies.

Also, a loss of sense of smell may have a profound effect on our quality of life, leaving us unable to enjoy pleasant smells such as new-mown grass, autumn leaves or highly scented flowers. Gone too may be the ability to recapture nostalgic memories previously recalled so readily, such as the scent of a particular perfume or the aroma of a favourite dish.

Can loss of sense of smell predict serious diseases?

Research results published in 2017 and 2018 suggest that losing our sense of smell can be a possible predictor of health risks, including a higher risk of Alzheimer's and a higher risk of dementia. Other studies also suggest that anosmia (the total loss of smell) may be strongly associated with a higher risk of mortality, being even more predictive of 5-year mortality risk than cardiovascular disease.

However, although many factors influence our sense of smell, we shouldn't assume that losing our sense of smell will automatically lead to health risks.

Diagnosis

If you have a loss of sense of smell or taste, it is important to obtain a proper diagnosis from an ENT (ear, nose and throat) or allergy specialist. Depending on the cause, they may be able to prescribe appropriate treatment.

You might also consider taking these actions:

- Avoid known triggers, like smoking and contact with allergens that cause rhinitis (like cat allergies or whatever you are susceptible to).

- Consider suitable adaptations. For example, switch to an electric cooker in place of gas, install smoke alarms, check and adhere to the ‘use by dates’ on food packaging.

- For personal hygiene, a regular routine for personal washing and bathing, change of clothing etc. may be more appropriate than relying on your sense of smell.

- To restore your enjoyment of food, consider adding more seasoning – particularly seasoning that is sharp and acidic, such as lemon juice – and being more liberal with spices.

Can we improve our sense of smell?

It seems that training our sense of smell may help restore it, particularly when it has been lost after a severe respiratory viral infection. A review of 20 studies, published in 2021, concluded that olfactory training may be an effective treatment for olfactory dysfunction.

|

‘Olfactory training’ involves repeatedly smelling four to six distinctly different odours such as cloves, roses, lemon and eucalyptus every day over a period of several weeks. Success depends on the duration of the training and the number of different odours used. Frontiers in Neuroscience (2021) |

The addition of topical steroids to the training programme showed a tendency for even greater improvement. Furthermore, a 2017 pooled analysis of 13 studies concluded that such training should be considered an addition or an alternative to existing smell treatment methods.

Conclusions

- Age is one of a number of factors that can reduce our sense of smell and taste.

- Losing our sense of smell and taste removes one of the ways our bodies can identify risk. It can also reduce our enjoyment of food and of life.

- Loss of smell or taste may be an indicator of future illness.

- It is important to see your doctor if you start to lose your sense of smell and taste.

- Training our sense of smell may help to restore it.

- If the loss of smell or taste isn’t treatable, then consider suitable adaptations, such as using an electric cooker rather than gas or adding more spices to food.

Reviewed and updated by Barbara Baker, December 2021. Next review date, November 2025.