Can mental activity, a healthy diet and an active social life reduce the risk of Alzheimer’s? Can smoking and depression increase the risk?

In 2017, The Lancet’s International Commission on Dementia Prevention, Intervention and Care reported that:

- Dementia is not an inevitable consequence of ageing.

- Nine potentially modifiable health and lifestyle factors, including mental, physical and social activity, early education and diet, might help prevent dementia.

- More than a third of dementia cases globally may be preventable by addressing these lifestyle factors.

This Age Watch article reviews the evidence for ways of reducing our risk of developing Alzheimer’s, including:

- What are the types of dementia?

- Is mental activity important?

- What is the brain’s ‘cognitive reserve’?

- How do mental activity and enriching your mind help?

- Is physical activity also important?

- Can diet make a difference?

- How does a social life help?

- What factors increase the risk of Alzheimer's?

What are the types of dementia?

Each type of dementia has its own causes and symptoms. Of the different types of dementia, Alzheimer’s disease is the most common, so this is the type of dementia we’ll focus on in this article.

Is mental activity important?

Alzheimer’s is a disease of the brain, so can keeping our brain active reduce the risk? Mental activity is one of the more promising areas suggested by research.

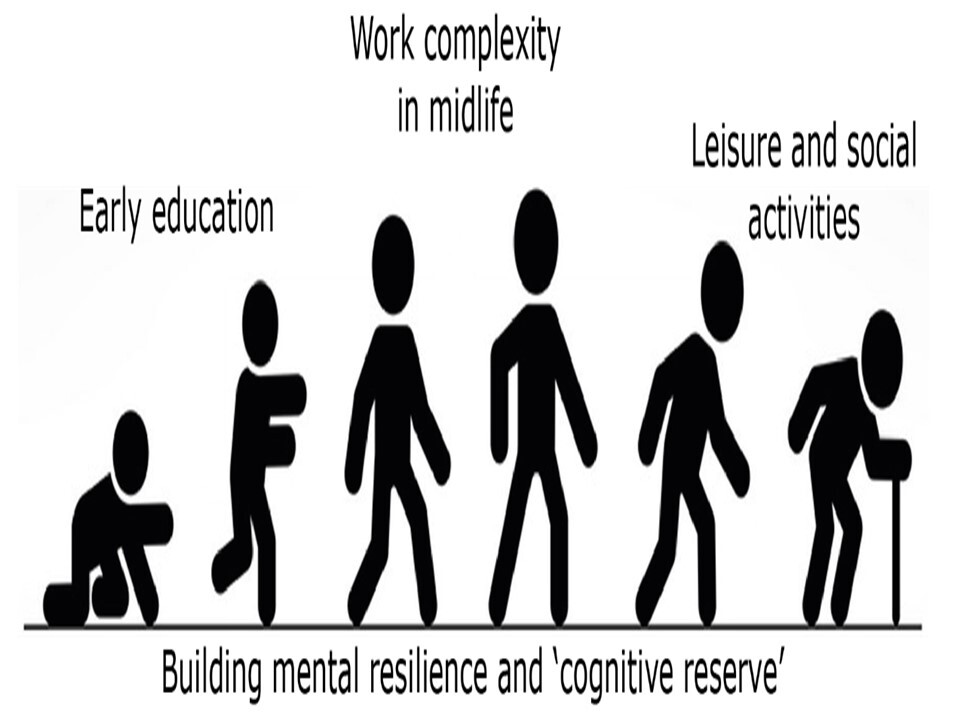

One interpretation is that if we stay mentally active throughout our lives, including developing new interests and skills, then this develops some form of reserve in our brain which helps protect against or compensate for dementia. This is known as the ‘cognitive reservehypothesis’.

What is the brain’s ‘cognitive reserve’?

An analogy that might help you understand cognitive reserve and why it is so important for our mental health, is to think of cognitive reserve as the ‘software’ that runs the ‘hardware’ of the brain. As the brain hardware ages and becomes less efficient, the cognitive reserve software finds ways of maintaining both brain efficiency and brain performance. High levels of cognitive reserve help us cope mentally as we age or become ill.

For example, a 2019 study of 2,556 cognitively healthy participants aged over 60 suggested that developing a healthy level of cognitive reserve might be particularly helpful for those with an increased genetic risk of dementia.

The study gave examples of activities that seem to contribute to building high levels of cognitive reserve:

More recently, a 2020 study in England, with 12,280 participants aged over 50 supported this finding. It concluded that individuals who had higher levels of education, who had worked in complex occupations and who enjoyed full and varied leisure activities, had higher levels of cognitive reserve, and as a result they showed a reduced risk of dementia.

How do mental activity and enriching your mind help?

One example of mental activity in practice is speaking more than one language. Several studies suggest that this helps protect our mental ability. For example, a study published in 2011 analysed brain CT scans found that people who could speak more than one language before they showed symptoms of Alzheimer's disease were able to adapt to more brain damage than those who spoke only one language.

Observational studies have suggested that bilingualism delays the onset of Alzheimer's symptoms by up to four and a half years. Other research, however, indicates that, although bilingualism delays the onset of symptoms, once Alzheimer’s is diagnosed in bilingual people, their decline to full-blown Alzheimer’s is much faster because by this stage the disease has reached a more severe level.

Enriching your mind in later life can also help protect your brain. A review in 2018 of published research found that adults suffering from Alzheimer’s who attended university classes increased their cognitive reserve and improved their brain function. Continuing education later in life is also associated with a lower incidence of dementia.

Is physical activity also important?

Until recently, physical activity was widely believed to be an important factor in reducing the effects of Alzheimer’s. However, in a long and detailed report, Alzheimer's Disease International (ADI) points out that most of the studies suggesting this association were conducted with older adults, and it could simply be that as people get older or develop Alzheimer's they exercise less. In other words, low levels of physical activity may be the natural result of ageing or Alzheimer's rather than being responsible for Alzheimer's.

An analysis of 19 studies, published in 2019, found that there was no direct association between physical activity and a reduced risk of dementia. The analysis did find an association, however, between physically inactive people and cardiovascular disease, which in turn leads to a higher risk of developing dementia.

These findings may suggest the potential for physical activity for helping in particular situations. ADI has identified that two of the factors with the strongest evidence for causing dementia (including Alzheimer's) are diabetes and hypertension (high blood pressure).

A report by the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges suggests that regular exercise can reduce the risk of type 2 diabetes by at least 30%. While a Chinese study with 512,000 participants, published in 2019, found an association between higher levels of physical activity, lower levels of sedentary leisure time and a lower risk of developing diabetes.

Similarly, a number of studies have suggested that exercise (provided it isn't too intense) is likely to reduce the risk of hypertension. So it is possible that there are indirect ways in which regular physical exercise might reduce the risk of developing Alzheimer's.

In an Age Watch interview on the possible ways of delaying the onset of dementia symptoms, Dr Louise Allan of the British Geriatrics Association advises, ‘There’s now so much evidence for the general health benefits of keeping physically active, and so few health risks, that it seems sensible to recommend physical activity.’

And a small study in 2015 suggested that physical exercise may make a difference by increasing the volume of the brain’s hippocampus in older women with mild cognitive impairment. The hippocampus is a structure embedded deep in our brains that is important for learning and memory and is particularly vulnerable to Alzheimer’s.

Can diet make a difference?

It is often said that what is good for the heart is good for the brain. We know that a healthy diet reduces the risk of heart disease, but can it also reduce the risk of brain disease?

We haven’t found much hard evidence relating to diet and dementia. However, one review of the evidence concluded: ‘Although there are no Alzheimer’s-fighting superfoods or sure-fire diet plans, long-term healthy eating habits can help promote good brain health, potentially slowing the development and progression of Alzheimer’s, along with other forms of age-related dementia.’

How does a social life help?

A 10-year study with 12,030 participants, published in 2018, found that loneliness was associated with a 40% increased risk of dementia, irrespective of gender, ethnic origin, education or genetic risk.

While loneliness can be different from social isolation, in that some people can be socially isolated without feeling lonely, for most people, social interaction seems likely to reduce the risk of dementia. This suggests the value of staying connected with your family and friends or reconnecting with them. Other ideas for increasing your social activity include joining a book club or a sports club, doing voluntary work, enrolling in adult education classes or getting involved in a community activity.

What factors increase the risk of Alzheimer's?

Genetics – Fewer than 1% of people have a particularly high inherited risk of dementia. This risk may occur earlier in life than usual, however, and in such cases even a healthy lifestyle is unlikely to protect you. In other cases, the disease may skip a generation, appearing again seemingly from nowhere, or it might not be passed on at all. A greater proportion of people have other 'risk genes', such as an increased risk, but no certainty, of developing dementia. In these cases, the Alzheimer's Society advises that you can reduce your overall risk by adopting a healthy lifestyle.

Smoking – Research indicates that smoking is a significant risk factor for Alzheimer’s. The Alzheimer’s Society recognises that smoking increases the risk of developing dementia by between 30% and 50%. On the positive side, if you stop smoking, it is thought that you can reduce the risk of developing dementia to the level of non-smokers.

Depression – Being depressed in late life is associated with an increased risk for all types of dementia, including Alzheimer's.

Seek medical advice if your depression continues. However, it is worth noting that physical exercise can help you if you have mild depression, and exercise may even stop you getting depressed in the first place.

Conclusions

- Mental activity is strongly recommended for helping to build your cognitive reserve – think about activities like learning a new language or a musical instrument, developing a new hobby or skill, attending an adult education class, playing board games or doing voluntary work.

- Social interaction also seems to be important – this suggests the value of maintaining relations with family, friends and neighbours, as well as starting new social activities.

- The evidence for physical activity and a healthy diet is less strong – however, there is so much evidence for their general health benefits and so few health risks, that it seems sensible to take some form of regular physical activity and to maintain a healthy diet.

- Avoid known risk factors – stopping or cutting down on smoking, and seeking help if you suffer from depression both help to reduce the risk of you developing Alzheimer’s.

Reviewed April 2020. Next review due March 2023.