Dementia

What is dementia? What are the main types, and how do they differ from one another? Can we protect our brains against dementia?

In this article:

- What is dementia?

- Types of dementia

- How many people in the UK have dementia?

- Why have dementia rates been falling?

- What are the main risk factors?

- Can we protect the brain against dementia?

- Conclusions

What is dementia?

The word dementia describes the symptoms experienced by people whose brain is not working properly.

They may have problems remembering, thinking and speaking. Their mood or behaviour may also change. Dementia is caused when the brain is damaged by diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease, or by strokes. The damage done to the brain is often visible in brain scans.

These diseases affect different parts of the brain and therefore affect people in different ways. Symptoms of dementia slowly get worse until they interfere with normal daily life. It is not something that happens to everyone as they get older, but unfortunately there is no proven cure yet, so actions to reduce the risk of dementia or to delay its onset are particularly important.

Types of Dementia

There are five main types of dementia:

- Alzheimer’s disease

- Vascular dementia

- Dementia and Lewy bodies

- Frontotemporal dementia

- Mixed dementia

The Alzheimer’s Society describes these main types of dementia and their symptoms as follows:

Alzheimer’s disease

More than 520,000 people in the UK have dementia caused by Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s disease is a physical disease that affects the brain in which connections between the billions of nerve cells that make up the brain are lost. This loss of connections is caused by a build-up of proteins which form abnormal structures called plaques and tangles. Eventually the nerve cells die and brain tissue is lost. People with Alzheimer’s also have less of some of the chemicals that send signals between nerve cells.

Symptoms, usually mild at first, can include memory loss, disorientation of time and space, difficulty organising and planning, confusion, difficulty finding the right words, difficulty with numbers and with money, changes in personality and mood, and depression.

Alzheimer’s is a progressive disease. This means that, gradually over time, more parts of the brain are damaged, and more symptoms develop and get progressively worse.

The life expectancy of someone with Alzheimer’s varies greatly from person to person. On average, people with Alzheimer’s live for 8 to 10 years after the first symptoms.

Vascular dementia

Vascular dementia is the second most common type of dementia (after Alzheimer’s disease) affecting about 150,000 people in the UK. Vascular dementia occurs when the blood supply to the brain is interrupted due to a blockage or a leakage of these blood vessels, causing cells to die within the brain. The symptoms of vascular dementia can occur suddenly, such as after a stroke, or over time, through a series of small strokes.

Symptoms can include slowness of thought, difficulty planning, trouble with language, problems paying attention or concentrating, and mood and behaviour changes. There may also be stroke-like symptoms, including muscle weakness or paralysis on one side of the body. Like Alzheimers’, vascular dementia is a progressive disease.

How long someone will live with the disease varies greatly from person to person. On average it will be about 5 years after diagnosis. The person is most likely to die of from a stroke or heart attack.

Dementia with Lewy bodies

Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) may account for 10-15% of all cases of dementia and is often mistaken for Alzheimer’s disease. Lewy bodies are tiny deposits of protein in nerve cells in the outer layers of the brain. These deposits are associated with a loss of connection between nerve cells, which then die.

Symptoms include problems with mental abilities, visual hallucinations, movement difficulties similar to those of Parkinson’s disease*, and sleep disturbance. DLB is a progressive disease.

On average, a person with DLB may live for about 6 to 12 years after the first symptoms.

*(Parkinson's disease also affects the brain. The main symptoms are shaking (tremors), slow movements and stiffness. Lewy bodies are also associated with late-stage Parkinson’s disease.)

Frontotemporal dementia

Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) is a less common type of dementia. It results from damage by disease to two sets of lobes (frontal and temporal) in the brain. This causes a loss in the connections between the lobes and other parts of the brain, and the death of nerve cells.

Memory loss isn’t usually an issue until the disease is at an advanced stage. Symptoms such as changes in emotion, personality and behaviour, however, are more typical. People with frontotemporal dementia appear to be less sensitive to other people’s feelings, as well as appearing cold and unfeeling. There may also be a loss of inhibition, resulting in behaviour that seems out of character, such as tactlessness or inappropriate remarks.

Some people with frontotemporal dementia also have language problems. This may include speaking less than usual, or even not speaking at all, or having problems finding the right words. FTD is progressive.

The life expectancy of a person with FTD varies from person to person and is affected by other factors such as a person’s age when first diagnosed and other health conditions.

Mixed dementia

At least one in ten people with dementia has more than one type of dementia. This is more common in those over 75 years. Alzheimer’s disease and vascular disease is the most common types of dementia that occur together.

In the later or more advanced stages of mixed dementia, the effect on the brain can be so significant that people are unable to recognise family or friends. They may also lose the ability to speak, become less able to move without help, become incontinent and lose their appetite and lose weight.

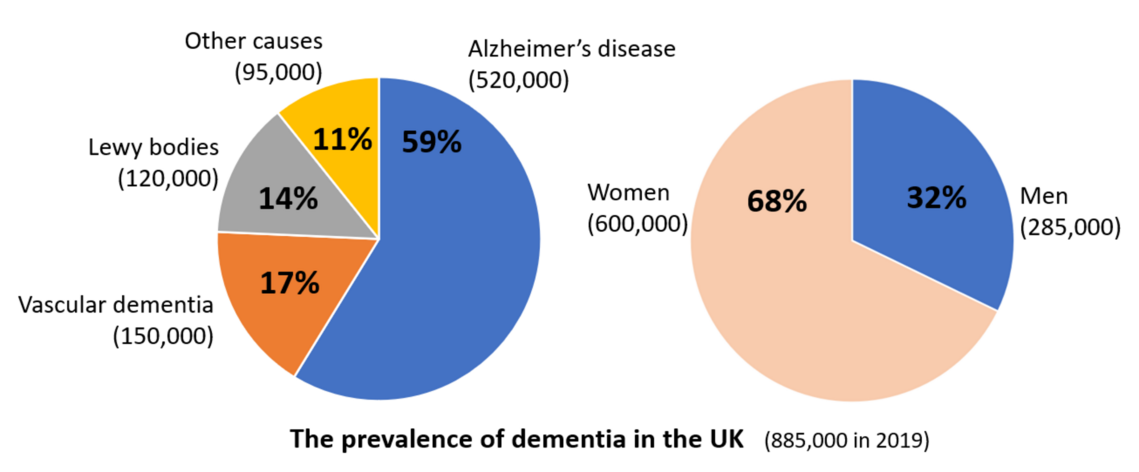

How many people in the UK have dementia?

It is estimated in an Alzheimer’s Society report that there are almost 885,000 older people living with dementia in the UK in 2019, of whom 84.7% (748,000) live in England. The vast majority of people with dementia are aged 65 or over. Two-thirds of people with dementia are women; over 600,000 women in the UK are now living with dementia, the leading cause of death in women in the UK.

Based upon the assumption that the population of older people will continue to increase, the report estimates that the number of people with dementia in the UK will increase to around 1.6 million in 2040. This estimate also assumes that an effective treatment for dementia doesn’t become available before 2040.

However, a systematic review published in 2018 reported that dementia rates in the UK (as a proportion of the total population) have in fact been falling since 2010. This trend may limit the suggested growth in dementia cases over the coming years. In other words, there will be more older people but a smaller proportion will develop dementia.

Why have dementia rates been falling?

Falling dementia rates are believed to be due to

- individuals’ actions to improve heart health by leading a healthier lifestyle (‘what is good for the heart is usually also good for the brain’)

- better education, as higher education is associated with a reduced risk of dementia. This is one of several factors believed to build a protective cognitive reserve that prevents or delays the onset of dementia. More than half of young people now go to university in the UK, suggesting this will become an increasingly important protective factor.

- taking part in mentally, socially and physically stimulating activities. For example, people who can speak more than one language show a delay in the development of dementia symptoms. This is sometimes referred to as an example of developing a protective cognitive reserve. However, bilingual people later go on to experience more rapid brain shrinkage than non-bilinguals, suggesting a more severe disease for a shorter time.

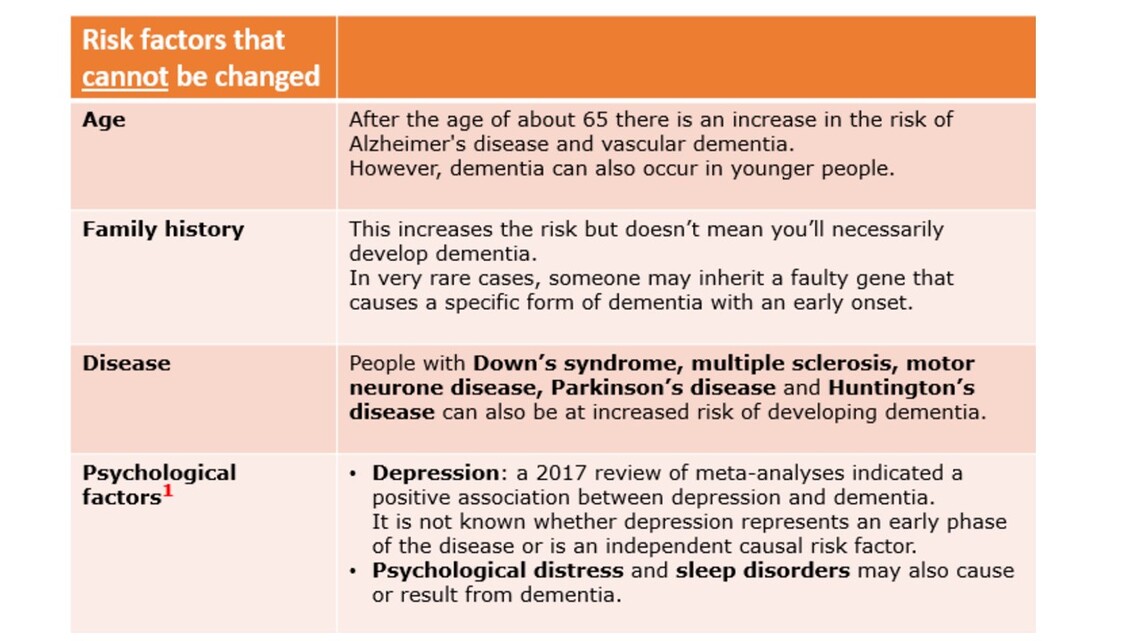

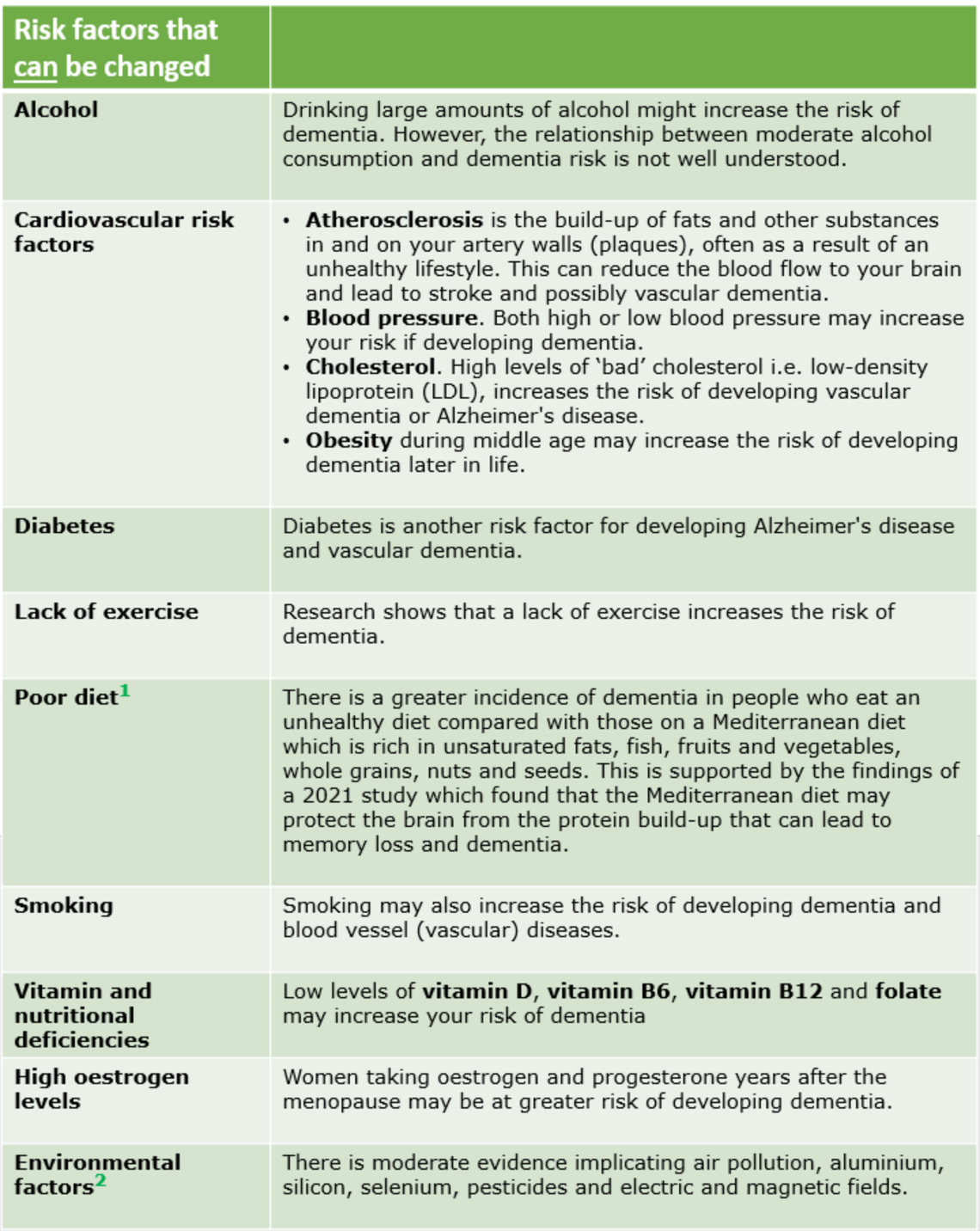

What are the main risk factors?

The two tables below list the main risk factors of developing dementia, This information is from Alzheimer’s Disease International and the Mayo Clinic.

Poor diet and environmental factors are the two main factors that can be changed.

Can we protect the brain against dementia?

The good news is that there are various steps we can take to reduce our risk of dementia and protect our brain health.

As indicated in the previous section, limiting alcohol consumption, not smoking, a healthy diet and taking regular exercise all reduce the risk of developing dementia.

A Mediterranean-type diet is a good example of a healthy diet. Getting enough sleep, reducing stress, making friends (to reduce loneliness and depression) and stimulating the brain through new interests, hobbies and skills also help reduce risk. Stimulating the brain helps build our protective cognitive reserve.

Conclusions

- There are many types of dementia (of which Alzheimer’s is the most common) and they affect the brain in different ways.

- There is currently no cure, so anything we can do to reduce the risk is to be recommended.

- We can’t control some risks, like age or a family history of dementia.

- However, a healthy lifestyle can reduce the risk – in particular, not drinking too much alcohol, not smoking, taking regular exercise, eating a healthy diet, maintaining a healthy weight, and keeping mentally active.

Reviewed and updated by Barbara Baker, August 2021. Next review date, June 2025.

__________________________

Other relevant articles on the Age Watch website:

- Mind: Are active brains more resistant to dementia?

- Mind: Memory aids for dementia

- Mind: What happens to our brains as we get older?

- Ageing: Healthy ageing – a life course approach

- Living longer: Look after your body

- Living longer: How long can we expect to live in good health

- Living longer: How can we stay healthy longer?

- Fitness: Exercise improves brain performance

- Illness: Can we reduce the risk of Alzheimer’s? (cognitive reserve)

- Diet: What is the Mediterranean diet?

- Diet: Mediterranean diet health benefits