Do we have a built-in body clock, and if so, what makes it tick? Does it affect our sleep, and what are the health implications?

- Do we have a built-in body clock?

- What makes our body clock tick?

- Does our body clock affect our sleep?

- What are the health implications of disruptions to our body clock?

- The effects of sleep loss on our health

- Might other factors be at work?

- A U-shaped effect

- Conclusions

Do we have a built-in body clock?

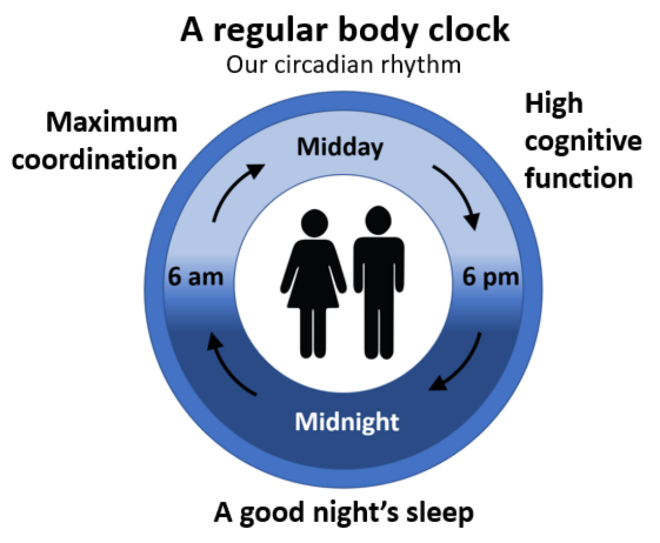

We each have an in-built body clock, which can be triggered by the sun rising and the sun setting. It usually tells us when it is time to wake up and when it is time to sleep, and it influences when we feel awake and when we feel tired.

If we ignore this natural body clock then problems can arise. For example, a greater proportion of night shift workers experience fatigue-related accidents compared with people who work in the day time. Similarly, people who work long hours and people who drive at night are also more likely to be involved in fatigue-related accidents. Also, our ability to perform maths calculations or other intellectual tasks between four o’clock and six o’clock in the morning is worse than if we had drunk enough whisky to be legally drunk.

These examples show that, like other animals and plants, we have a built-in body clock, which probably evolved to help our bodies make the most productive use of daytime for activity and night time for sleeping. When our body clock is upset, for instance as a result of a long-distance flight to a different time zone, we often experience physical and mental symptoms, typically described as jet lag.

What makes our body clock tick?

Over many thousands of years our bodies have evolved to respond to the cycle of day and night, light and darkness, such that light and darkness are the two main triggers.

However, the development of artificial lighting and its availability 24 hours a day is one of a number of factors that may be potentially disrupting our natural body clock.

Does our body clock affect our sleep?

Yes. That’s why people who experience difficulty sleeping are sometimes advised to spend time outside during the day. Daylight provides the light cues our bodies need for staying awake. In the evening, the recommendation is to avoid blue light – for instance from computer screens, tablets and mobiles – before sleeping, and to sleep in a room which is as dark as possible. Darkness provides the cue our body needs to reinforce that this is the time to go to sleep. Some sleep problems seem to be due to modern lighting and communications technology (e.g. generating increased blue light from computer and mobile screens), long-haul flights and night shift work, all of which can potentially confuse our natural body clocks.

Conversely, in a small research trial published in 2017, patients with insomnia who wore amber-coloured lenses rather than clear lenses for a couple of hours before going to bed were able to sleep better. This finding suggests that the type of light we are exposed to before bedtime affects our sleep patterns.

What are the health implications of disruptions to our body clock?

The health implications are now beginning to be recognised and researched. For example, Oxford University has appointed a Professor of Circadian Neuroscience, and there is growing interest in ‘chronotherapy’, a method of continuously adjusting abnormal sleep patterns until they coincide with the natural circadian rhythm. Using chronotherapy and chemotherapy together in the treatment of cancer has helped to identify the optimal time to administer chemotherapy for the best treatment outcomes. Clinical trials suggest that administering medication for cancer at the time it is most likely to be tolerated within the circadian cycle has two advantages: patients tend to experience less severe side effects and the medication usually achieves the best anti-tumour activity.

Our moods and mental health may also be affected if our body clocks are disrupted or upset. In a small study in 2018, it was found that sleep disruption (i.e. a disruption of our circadian rhythm) is a core feature of mood disorders and is associated with a higher risk of depression, mood instability and even lifetime bipolar disorder.

The effects of sleep loss on our health

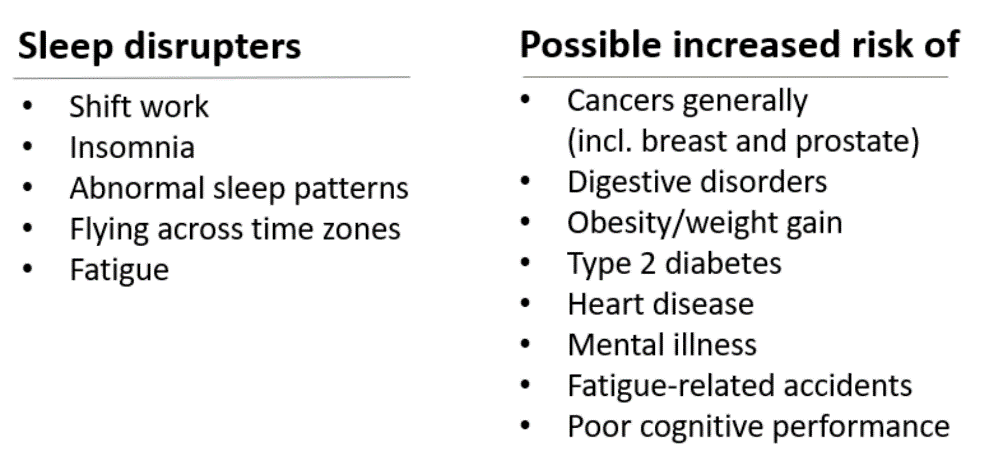

Disruption to our body clock, and the consequent sleep loss, can increase:

- the risk of breast cancer (as seen, for instance, in studies of nurses and flight attendants).

- the risk of prostate cancer (as seen in studies of airline pilots, flight attendants and shift workers).

- the risk of cancer more generally.

- the risk of digestive disorders.

- the risk of mental ill health.

Night shift work is one clear example where the body’s natural body clock is disrupted. A 2018 article in the British Medical Journal reported that night shift work had been linked with an increased risk of sleep loss, occupational accidents, obesity and weight gain, type 2 diabetes, coronary heart disease and several types of cancer.

Might other factors be at work?

A number of other factors might influence how well we sleep. For example, some medical conditions and some medications may disrupt our sleep patterns. Also, people with lower socio-economic status may be more vulnerable, for instance because they may have to work longer and more anti-social hours and may sleep in noisier environments. However, many studies now try to take account of other possible factors (called ‘confounders’ by researchers) and often find that lack of sleep has an independent effect in its own right.

A U-shaped effect?

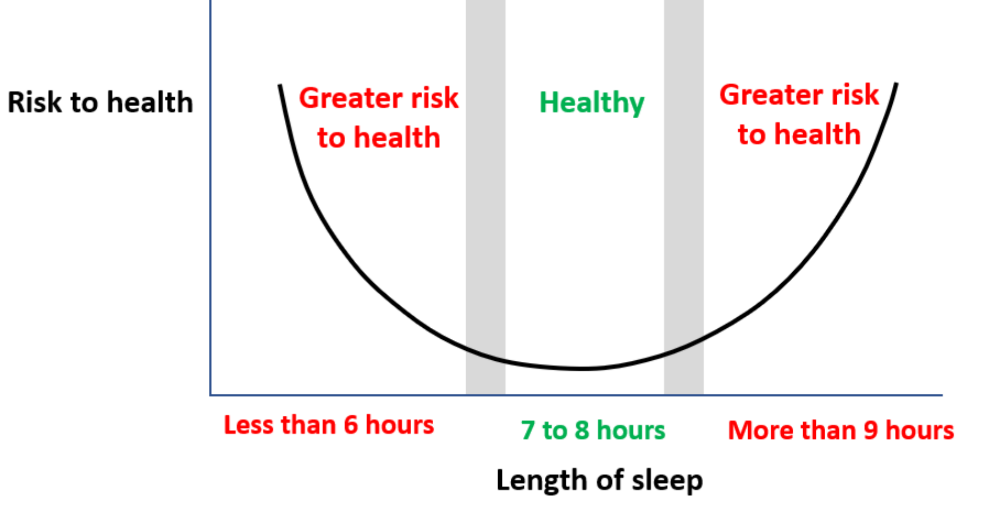

|

A healthy level of sleep is 7 to 8 hours per night. |

Some studies have suggested that too much sleep as well as too little sleep can indicate health risks (what researchers call a ‘U-shaped’ effect). This may apply to:

- Deaths from all causes: insufficient or prolonged sleep may increase all-cause mortality, with women being more affected than men.

- Heart disease: both ‘short sleepers’ (less than 6 hours sleep) and ‘long sleepers (more than 9 hours) showed higher risks of heart disease: 20% and 34% higher respectively.

Conclusions

We all have a natural body clock. So, where possible, we need to work with it to get an optimum 7 to 8 hours sleep per night. To give our body clock the cues it needs we can:

- Spend time outside during natural daylight hours.

- Avoid blue light before sleeping and background lights while asleep.

- If possible, avoid night shift work or work that induces regular sleep disruption.

- Change our lifestyle habits so that we can get a good night’s sleep regularly (i.e. between 7 and 8 hours per night).

__________________________

Other relevant articles on the Age Watch website:

- Ageing: Healthy living

- Living longer: Look after your body

- Mind: How much sleep do we really need?

- Mind: Sleep

Reviewed August 2020. Next review due, July 2024